Fiona Moore’s Shelfie

For this shelfie, I’m not going to show you my fiction collection. Instead, I’m going to show you some of the books I use when writing my books and articles on SFF movies and television (or “telefantasy”, as it’s sometimes known, so as to include SFF-adjacent series like The Avengers or Murdoch Mysteries), why I own them, and what’s important about them.

My background in researching TV also informs my other writing. When I’m writing a novel or a story, I’m always thinking in terms of pacing individual episodes and how they fit together to form a whole arc. I also think about casting, and about my fictional “budget”: I could theoretically take my stories anywhere, but if I’m thinking “one or two locations, five main cast members and two guest stars…” it helps me to focus. So let’s look at how I got there…

Television Programme Guides

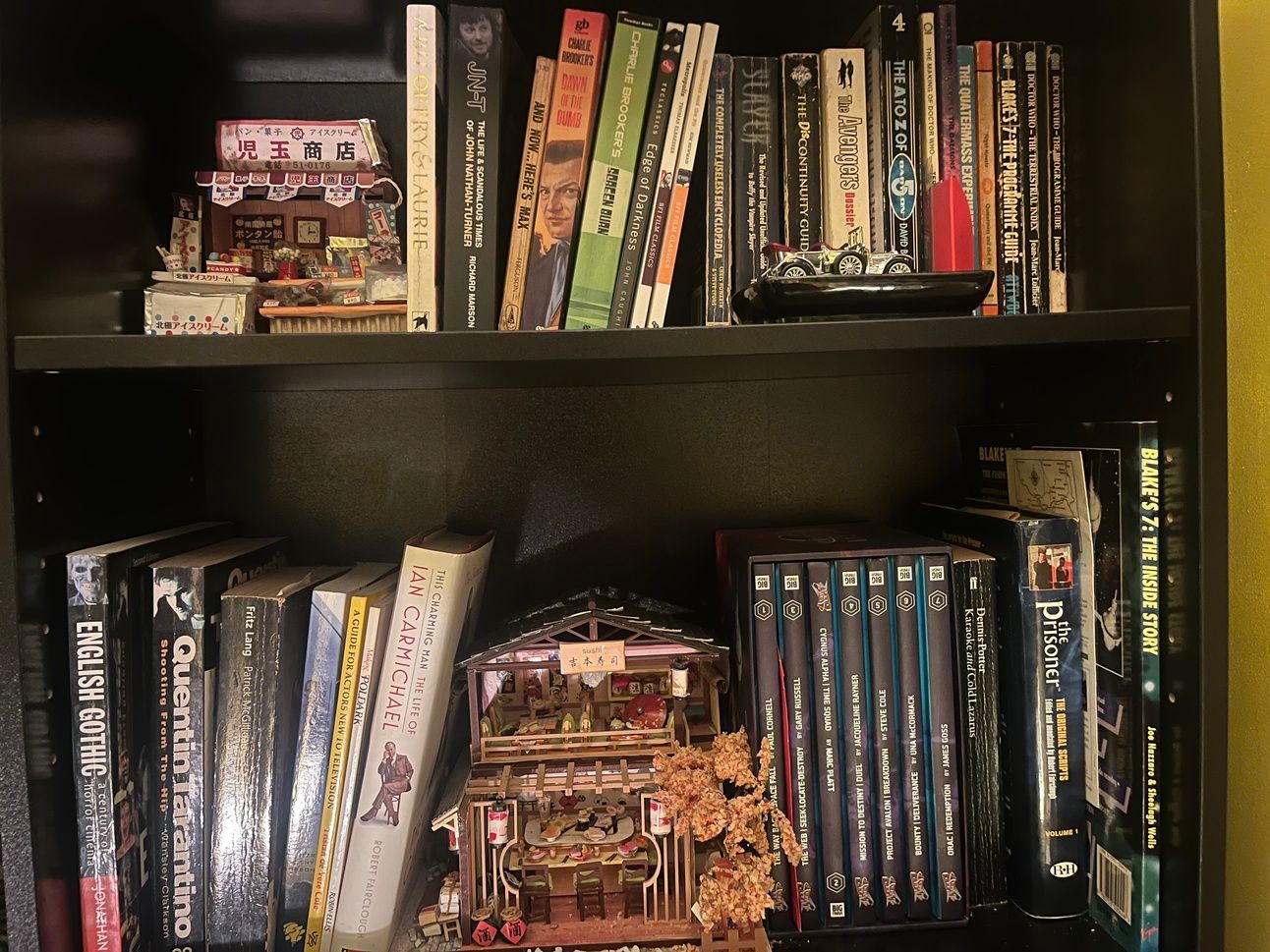

The first three guides from the right of the top shelf are official BBC programme guides (and a programme supplement) for Doctor Who and Blake’s 7. If you were a kid or a teenager who was into television in the pre-videotape era (or, like me, when videotapes were a thing but were expensive and hard to find), this was the sort of book you had to have. Paperback-sized guides to a TV series with ridiculously basic information, just cast lists and synopses, and a lot of that not very accurate either. But, as you can see from the worn-to-rags condition of the guidebooks here, TV nerds of that era would take what they could get.

And then those TV nerds grew up.

And the home video, and later DVD, industries boomed, and people put up websites, and so TV nerds no longer needed or wanted synopses and cast lists. Which is when you start getting those other guidebooks further along: the ones with titles like Doctor Who: The Discontinuity Guide or The A to Z of Babylon 5 or Slayer. These are longer, and may or may not be official, and are written by TV nerds, and so are full of the sort of detailed information about productions and their histories that nerds tend to like. Plus bloopers and continuity and other things to watch out for.

(And somewhere in there, you also get Doctor Who: The Completely Useless Encyclopedia, which looks like that sort of guidebook and is in fact a scathing and completely hilarious parody of them. Seek out a copy if you can.)

But now that you can get all of that all over the Internet? That’s when you start to get books like the kind I write, talking not about facts and figures, or histories, or things to watch out for, but essays about worldbuilding, criticism, politics and society.

Also The Life and Scandalous Times of John Nathan-Turner. But as well as a sensational biography of Doctor Who’s longest serving producer, that book provides invaluable details about the British television industry in the 1960s through 1980s: a period of creative ferment, fuelled by the work of LGBT+ people, women, ethnic minorities, Jewish people, Buddhists and Muslims. Sort of puts recent complaints that modern Doctor Who is “woke” into context.

Fritz Lang

On the top shelf, there’s a BFI Guide to Metropolis, and on the lower one, McGilligan’s exhaustive biography of its director, Fritz Lang. Metropolis is my favourite movie, in part because no two versions are ever the same. The original was lost, meaning that only a cut-down 90-minute version made for the US market survived, but over the years people added in found footage, or reordered things to make more sense. And since it’s silent, you don’t have to just use the original soundtrack; Moroder famously did a techno version, and I’ve seen the movie with accompaniments by a free jazz band and by an Irish harp. It’s fitting because the movie itself is one with resonances all over the political spectrum. These days, I think one could read it as a warning of what happens when billionaires form alliances with vindictive tech-bros and try to “disrupt the workplace”, and how the intellectuals and the workers need to come together to fix the damage.

Dennis Potter, David Lynch and Troy Kennedy Martin

You’ll notice several Faber scripts by, and critical works on, the above three people. All of them were key figures in television history in their respective countries, because they saw television not just as a cheap knockoff of theatre or cinema, but as a medium in its own right, with its own strengths and weaknesses. The subsequent attempts to turn Pennies from Heaven and Edge of Darkness into movies make it all to clear that these series are great because they’re made for television, not despite it.

Watching Twin Peaks is like watching a medium in transition. You can see in it the seeds of the American art television boom of the 2000s, but also made by people still thinking in terms of the 22-episode, reality-grounded, evening comedy-drama series. You can see errors in pacing and timing that wouldn’t happen ten years later. And so, you can see a whole industry taking notes, looking at what Frost and Lynch achieved and where they slipped, and building something new and incredible out of it.

Tiny Shop and Tiny Sushi House

Finally, you will also notice two miniature buildings. This is because I also make miniatures. What does that have to do with writing, you might ask? I find that part of the process of making the miniatures is thinking about the people who would have lived there, and trying to tell their stories through the visual arrangement. That little sweet shop is run by an elderly couple, in the same way they have for the past forty years. He is thinking of retiring and handing over to his eldest son, but he’s worried that his daughter-in-law would pressure him into selling up and taking a franchise with a chain store. The sushi restaurant is a local institution; it’s near a movie theatre and everyone always comes there before the movie or afterwards, to look at the posters and order their favourite dishes. It’s storytelling in a different form, and I get new ideas every time I look at them.

And now we’re back to fiction again….

Fiona Moore is a BSFA Award winning writer and academic whose work has appeared in Clarkesworld, Asimov, Interzone, and six consecutive editions of The Best of British SF. Her most recent fiction is the novel Rabbit in the Moon and her most recent non-fiction is the book Management Lessons from Game of Thrones. Her publications include two novels; five cult TV guidebooks; three stage plays and four audio plays. She lives in Southwest London with a tortoiseshell cat which is bent on world domination and a sealpoint cat who isn’t that bothered. More details, and free content, can be found at www.fiona-moore.com, and she is @drfionamoore on all social media.

Shelfies is edited by Lavie Tidhar and Jared Shurin. Join us on Instagram at @shelfiesplease.