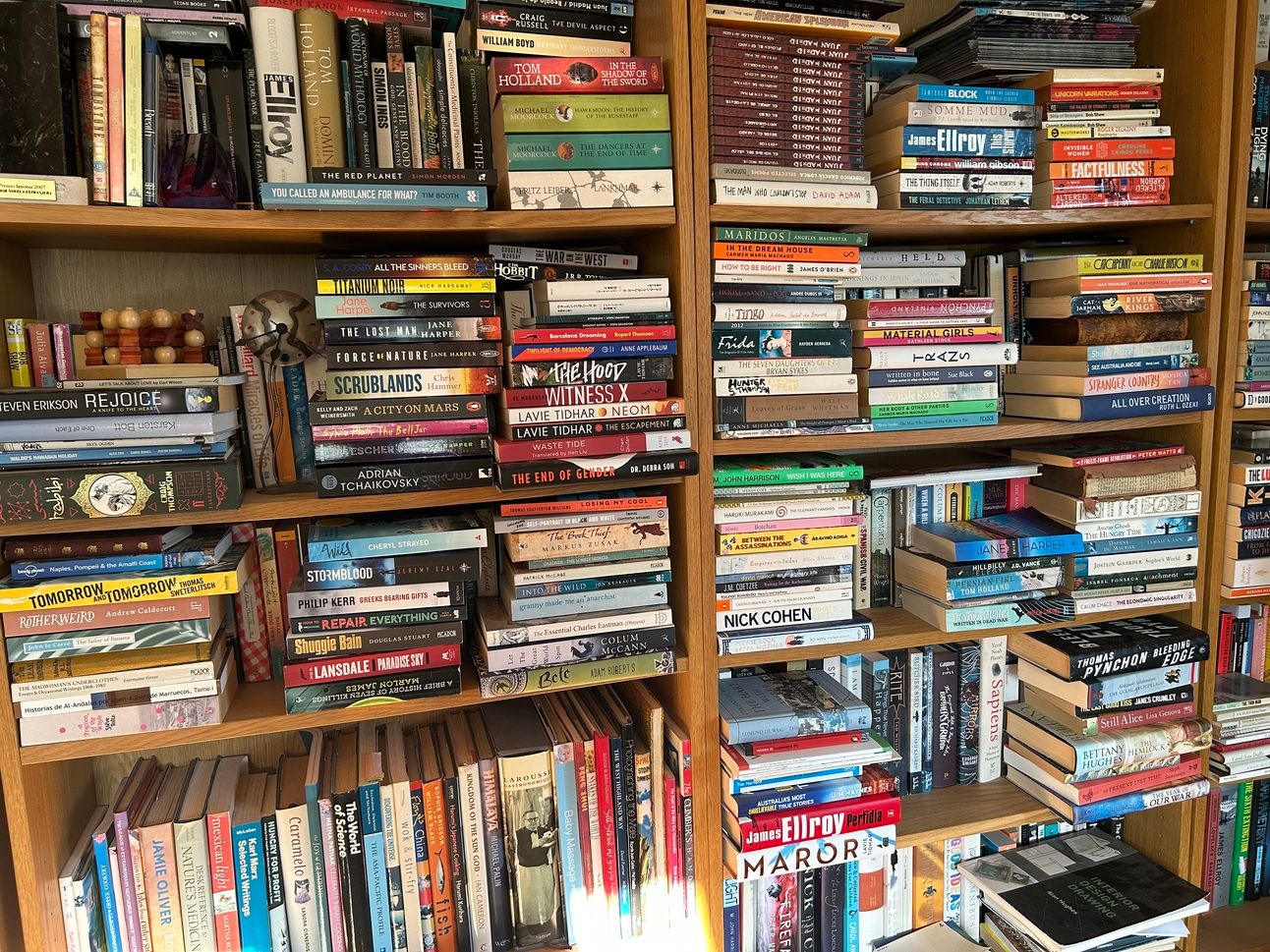

Richard K. Morgan’s Shelfie

To borrow from the great Ian Malcolm in Jurassic Park, Life, uh, finds a way - in this case, to, uh, fuck up your book-shelving.

Some time back in late 2018, after a frenetic series of house moves, I finally attempted to unpack our books, most of which I hadn’t seen since I took them off our majestic, three metre high shelves in our majestic Glasgow Victorian tenement flat three years previously.

We’d ended up moving to an old farmhouse in the back arse of nowhere which was actually a bit larger than the Glasgow flat. But it wasn’t Victorian, it was a Georgian/Jacobean mashup, and the sheer lack of high ceilings or grandly appointed rooms with decent wall space led to the miserable cramming chaos you see here. Fiction, non-fiction, paperback, hardback, publishers’ ARCs, special editions, graphic novels, even a few DVDs (remember them?). Some of my wife’s stuff too - she reads on Kindle, and is less sentimental about ownership or display, a lot of hers are still in boxes - even some of my own stuff in foreign edition. Books I’ve bought at every point in my life dating back to my teens. Books I’ve loved. Books I’ve thought important. Good books, so-so books (there are no actually bad books here - those get shipped out, given to charity, inevitable victims of a shelfish - arf, arf - Darwinian ecosystem that takes no prisoners.) And, of course, every book bought since that day in 2018 has had to fight tooth and nail for its space on one of these shelves too.

Behold the resulting slaughter!

Order, what order? I started out well-intentioned, but any order is now all but obliterated by subsequent layers, trowelled on like bricks in Poe’s The Cask of Amontillado. Some of those are recent acquisitions, some simply re-reads put back in a hurry. Take Thomas Pynchon’s Vineland, for example. There it is, right hand case, second shelf down, middle stack, and not even right way up, tossed there after I finished what must have been at least my fourth or fifth re-read. Among purist Pynchonophiles, Vineland doesn’t rate that highly, perhaps due to its relative accessibility and straightforward barrelling rock-n-roll storyline - Gravity’s Rainbow, it ain’t. But it is among my favourites, for almost exactly the same reasons. And with its eviscerating takedown of Reagan-era right wing backlash, alongside a more gentle critique of the idiot leftist tendencies that stood not a hope in hell of stopping the tide, now more than ever, Vineland is a prescient, needful read.

Also discoverable in this segment, on the shelf above - Somme Mud by E. P. F. Lynch, a harrowing diary of the First World War as recorded by a young Australian infantryman shipped halfway round the world to serve King and Country in the trenches of France and Flanders. There’s an unvarnished honesty - almost an innocence - and an understated grit to this account, which for me lifted it well above the bulk of non-fiction I’ve read on the Great War. Somme Mud was invaluable in researching my most recent novel, No Man’s Land. Remember, this coming October - each time you wince at some trench related horror in No Man’s Land, chances are it had its genesis in some real event narrated here by Lynch.

Speaking of Aussies, you’ll also see a fair bit of antipodean crime bestseller Jane Harper scattered across these two cases. She’s a relatively recent discovery for me. Following a chance encounter last year with her debut novel The Dry (not seen here, shelved somewhere - christ knows where! - else) I ended up simply buying everything she’s written since. Harper has a deceptively simple narrative style and a penchant for plots that reveal unexpected brutalities hidden in plain view. As a result of this, and despite Harper’s choice of almost exclusively male protagonists, there is a powerful feminist slant to the stories she likes to tell. Of the other titles you see here, all are strong, but it’s The Lost Man - left hand case, second shelf down - which is, IMHO, the pinnacle of her work so far. An immensely subtle slow burn, with a cast of characters and locations so sparse it could almost be a stage play, The Lost Man works through a tangle of revelations to a devastating conclusion that you will, in the final pages, kick yourself for not seeing from the start.

Okay, running out of word count here - last shout-out goes to the venerable gentleman in two-tone shades of green, left bookcase, top right. Two volumes from the collected works of the illustrious Michael Moorcock, a massive early influence on my growth as a writer. Hawkmoon: The History of the Runestaff - published back then as four individual slim volumes - was for me, aged about nine, my springboard into the world of SFF. It may also, thinking back, have triggered my love of beginning narratives en media res - I accidentally read Volume II: The Mad God’s Amulet first, then had to backtrack to The Jewel in The Skull. (Not so easy to do in those pre-online days - remember when you had to trog around to multiple bookshops trying to find what you wanted?) And then there’s The Dancers at the End of Time - the polar opposite of Hawkmoon. Light-hearted versus intense, comedic versus grim, and yet somehow every bit as engaging, even for the mutinous pre-teen I then was. I came to Dancers about two years after Hawkmoon, having in the interim burned through every Moorcock tale of grim swordsmen and sorcerers I could lay my eager hands on. Hmm - so what’s all this, then? Out went sword and sorcery slaughter, in came decadent comedic escapades in a paradise of the senses - breakfasting off heroin in aspic, riding godlike chariots through the air to endless flamboyant parties, bouts of sex with your own mother, who, it transpires, only created you in the first place as an idle experiment in making children “the way the ancients did it”. Wow! Mind - blown! I mean, alright, stuff that might not seem all that transgressive these days, but hey, I was eleven, man! So thanks Mike - never been the same since!

Richard K. Morgan

Richard K. Morgan is the acclaimed author of ten novels - No Man’s Land, Thin Air, The Dark Defiles, The Cold Commands, The Steel Remains, Thirteen, Woken Furies, Market Forces, Broken Angels, and Altered Carbon, a New York Times Notable Book that won the Philip K. Dick Award in 2003. In addition to his novels, Richard is the author of two Black Widow graphic novels for Marvel - Homecoming and The Things They Say About Her - and was the lead writer for two video games, Crysis 2 and the 2012 re-boot of the nineties classic Syndicate. He has served as a consultant in the video games industry since 2008, and is currently a Development Director at Gunzilla Games.

Shelfies is edited by Lavie Tidhar and Jared Shurin.

Join us on Instagram @shelfiesplease.